Still Here: How Colonialism Keeps TB Around

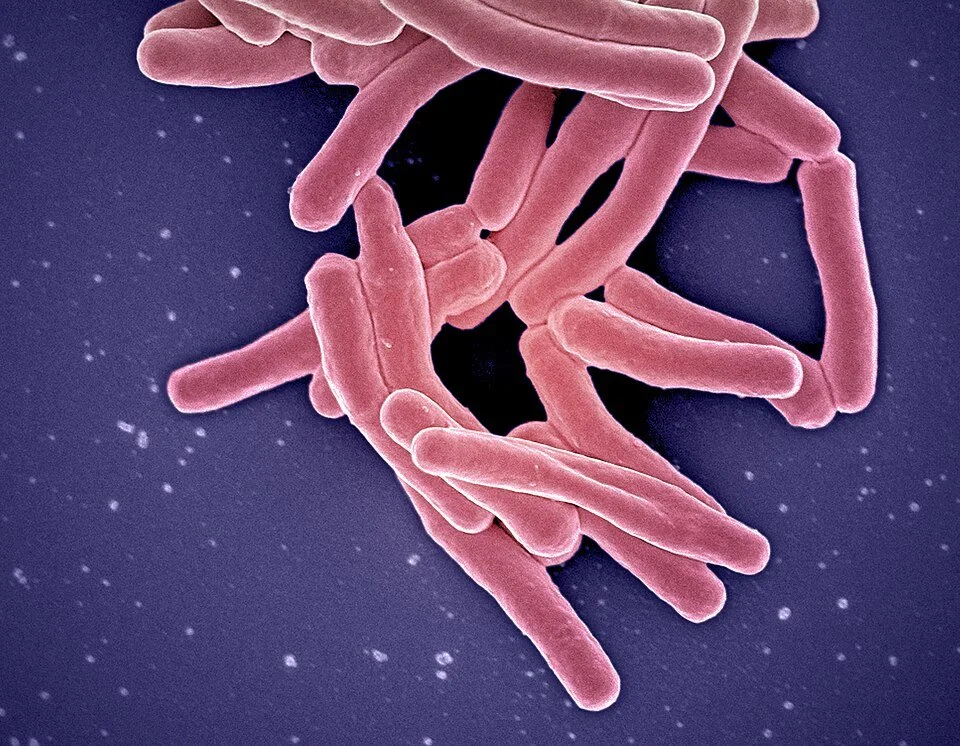

Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license

By Hillary Wright

Tuberculosis (TB) is an ancient, globally endemic disease with a long and complex history. Once known as "consumption" or the "White Plague," TB is caused by the airborne bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Despite significant global health advances and effective antibiotics, its persistence, latency, drug-resistant strains, and uniquely social character keep it as a leading infectious cause of death worldwide.

Today, it is estimated that 25% of the world’s population has been infected with TB. Most cases of TB infection go unnoticed, and only 5-10% of those infected will ever face symptoms and develop active disease.

The progression from dormant to active disease is social in nature and influenced by factors such as poverty, overcrowding, food and energy insecurity, barriers to accessing clean drinking water and healthcare, stigma and trauma, as well as socioeconomic inequalities, racism, and discrimination.

The historical trajectory of TB in Canada, particularly its disproportionate impact on Indigenous populations, serves as a poignant illustration of these social determinants at play. The following sections explore this history and its enduring legacy, examining how colonial policies shaped the endemic and continue to fuel the contemporary disparities.

History of TB “Care” in Canada

TB was a major public health concern from the late 19th through the 20th century. Although the disease affected the general population, rates of active TB were undeniably higher among Indigenous groups, particularly Inuit, and children within the residential school system. Thus, a political and social discourse emerged that coined TB as an “Indigenous” disease, coupled with harmful colonial stereotypes of Indigenous Peoples as less civilized.

Against medical advice, in 1946 the Canadian Government expanded the Indian Health Service to establish a network of southern, segregated Indian Hospitals and TB Sanatoriums. These hospitals were the site and result of paternalism, prejudice, and fear. Indian Hospitals and TB Sanatoria worked together to place the health and wellbeing of Inuit, First Nations, and Métis in the hands of the federal government – it removed their care from provincial jurisdiction and brought it under federal mandate.

Closely tied to the residential school system, many children were uprooted from their schools and homes and forced into lengthy ‘treatment’ and confinement at these supposed institutions of ‘care.’ Such institutions of care were used as tools for the broader Canadian health system to expand and modernize, while leaving Inuit, notably, and First Nations and Métis behind.

Many of these institutions were understaffed and overcrowded. Physicians and staff rarely knew how to communicate in the languages of their patients, and there have been a range of accounts of abuse, neglect, and even medical experimentation. There were two widely used antibiotic treatment protocols at this time. The first of which was administered through a painful injection administered through a needle, and the other was a round of pill-form antibiotics. Ideas of Indigenous patients as less responsible and cooperative meant that they were often subjected to the painful injection of antibiotic treatment. Many of the accounts of these patients describe having no clue why they were being injected, or what consequences of this often scary and painful treatment were.

Others were taken to the hospital for ‘treatment’ only to never be seen or heard from again. In many instances, patients were not allowed to see their friends and families, to speak their language, or engage in cultural practices.

Most of the children treated in these institutions live to tell the tale today. In many cases, the children never returned home, and when they did, they had lost their ability to communicate effectively after extended periods of isolation and separation from their culture. In essence, the practices of these institutions not only reflected colonial conceptions of medicine but also an effort to erase cultural diversity. The actions and design of the Sanatoria and Indian Hospital system were ones that too often constrained the practice of free will and self-determination, and that isolated Inuit, as well as First Nations and Métis, from accessing their support networks and community.

Contemporary Issues in TB

Forty years after the closure of the final Indian Hospital, major developments in health care and health policy have significantly reduced the burden of TB in Canada and abroad. On the surface, Canada appears to have TB well under control with only 5.5 new or relapsed active cases per 100,000 people (2023), compared with the global average of 101 per 100,000 (2023).

However, despite TB’s relative control in the general population, Inuit and New Immigrants in Canada experience some of the highest TB incidence rates in the world. For example, the TB incidence rate in Nunavik, the portion of Inuit Nunangat located in Quebec, exceeds 600 per 100,000. This rate is roughly 1,000 times greater than that of the Non-Indigenous Canadian-born population. More broadly, the TB incidence rate for Inuit across the country is 202.8 cases per 100,000.

Dr. Yassen Tcholakov, the Clinical Lead in Infections disease at the Nunavik Department of Public Health, as well as an Assistant Professor in the department of Global and Public Health at McGill University, noted:

“The presence of TB transmission and the incredibly high rates of disease in indigenous communities in Canada is a stark reminder of the inequities caused by colonialism that still affect current-day populations who are historically underserved, with limited access to healthcare, education, and economic opportunities, perpetuating cycles of poverty and health disparities. We know how to eliminate this disease, as demonstrated across the rest of Canada and in other resource-rich health systems, where TB has been effectively controlled through investments that addressed the social determinants of TB, including housing, nutrition, income security, and access to education and through universal access to timely diagnosis, uninterrupted treatment, and comprehensive patient support embedded in primary health care.”

Dr. Tcholakov’s comment reflects the entanglement between health care and politics, between tyranny and diagnosis, and between colonial governance and supposed ‘care.’ While doors closed in the 1980s, the mark of the segregated Hospital and Sanitoria system persists in present-day discrepant TB incidence rates and experiences of care. In 2018, the federal government published The Chief Public Health Officer’s 2018 Report on TB that officially recognized the disease as “social,” – a disease that is deeply affected by structural and social determinants of health (poverty, overcrowding, food and energy insecurity, barriers to accessing clean drinking water and healthcare, stigma and trauma, as well as socioeconomic inequalities, racism, and discrimination).

As Dr. Tcholakov notes, the federal government is well aware of how to deal with TB but yet fails to do so.

This final remark, and the closure of this piece, lead to a call to action. Radha Jetty, Chair of the First Nations, Inuit, Métis, Health Committee, urges policymakers, politicians, doctors, and civilians to work towards a better future. In essence, Jetty asks that we collaborate with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis; seek out and share culturally appropriate information; build and maintain culturally safe spaces for care; and address the Social Determinants of Health that disproportionately affect First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.

Hillary Wright

is a fourth-year undergraduate student, studying Economics (Arts) at McGill University. She complements her primary curriculum with minors in History and Health Geography. Hillary is from Ottawa, Ontario and shares a deep passion for health policy and health care systems, while considering the socio, political, economic, and environmental influences on health. She looks forward to pursuing a career in health policy and health research.