Loss of Measles Elimination Status in Canada

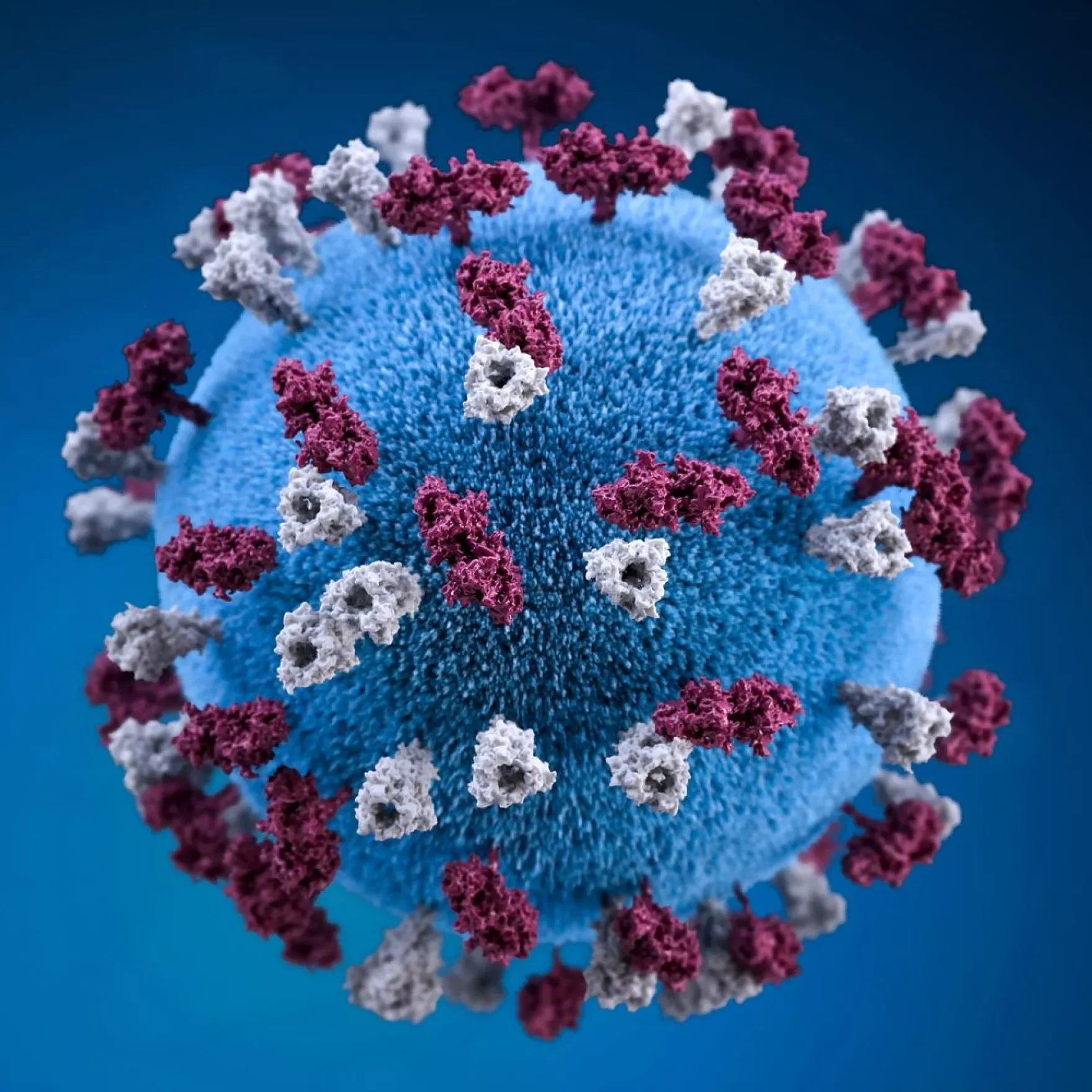

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention rawpixel.com

By Becca Winkelaar

When Elimination Isn’t Forever

On November 10, 2025, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) notified the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) that Canada had lost its measles elimination status—defined as the absence of sustained domestic transmission of the disease—following a review of data confirming ongoing circulation of the same measles virus strain for over a year. It was a stark reminder that measles is not an ailment of the past—it is very much part of our present, with serious implications for our future.

The news landed in very different ways. I spoke to people who were confused, having long grouped measles with “old-timey diseases”—vaccine-preventable illnesses that Canadians are fortunate to barely think about anymore. And they are not entirely wrong: Canada eliminated measles in 1998, when widespread MMR vaccination drove case numbers down to an average of just 91 per year. So, what happened?

Why the News Felt Shocking, and Why It Shouldn’t Have

For those who follow or work in public health, the announcement felt far less surprising. Beginning in October 2024, a large, multijurisdictional measles outbreak spread across the country, with cases emerging in multiple provinces and territories across Canada. According to the latest federal report, 5,298 measles cases have been reported across 10 provinces and territories in 2025 alone, with 37 new cases in the most recent week of available data (November 23–29).

Before this, some experts suspected Canada was heading toward trouble. As part of a Zoom interview, I spoke with Dr. Paul Leguerrier, Dr. Véronique Morin, and Dr. Chloe Mancini, the two former responsible for managing vaccine-preventable diseases in Montréal and affiliated with Université de Montréal and McGill respectively; and the latter their resident.

Physician at the Montreal Public Health Department (MPHD), Dr. Leguerrier told me that he and his team had been keeping an eye on measles’ resurgence “for probably close to two years now.” He pointed to accelerating activity in Europe and the U.S., smaller outbreaks in Canada in late 2023 and early 2024, and the spread of cases across provinces later that year. “We’ve been watching this,” he said, and in retrospect, those warning signs might have marked a window where targeted vaccination catch-up efforts could have reduced the scale of the outbreak.

Still, the anxiety around this outbreak is not mere frustration at a disease we thought we buried. It is a troubling hint of the vaccine-resistant future that may be waiting ahead.

Watching the Storm Gather

The answer lies not in a sudden change in the virus itself, but in population-level immunity slipping below the threshold needed to prevent sustained transmission. The first thing to be aware of is the disease’s severity: measles is not “chicken pox-adjacent.” It causes high fever and a dramatic red rash, but it can also be fatal. The CDC estimates that 1 to 3 of every 1,000 infected children die during the acute phase. However, recovery is not always the end of it. The disease can completely wipe out the immune system’s “memory” of past infections, a phenomenon known as immune amnesia, leaving people vulnerable to illnesses against which they were previously protected.

The second, more reassuring part is that measles is entirely preventable. The measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine or the measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine—typically given in two childhood doses—provides lifelong immunity for most people. Adults can receive catch-up doses if they miss part of their schedule. These vaccines are incredibly effective, and they are the reason Canada eliminated measles in 1998.

The Paradox of Prevention

So, the natural question is: If we have a great vaccine, why is measles back? Dr. Véronique Morin explained how the success of the vaccine is part of the problem: “For many younger adults, measles is a disease that they've never seen, precisely because vaccines have worked so well.” Without lived experience — and the fear of an outbreak — people easily underestimate the value of consistent vaccination.

Indeed, Dr. Morin said that declining vaccination rates are the sole driver of Canada’s current outbreak. And with measles, one of the most contagious diseases on Earth, even small declines matter: measles’ transmission rate is above 90–95%. One case can produce up to 18 secondary infections, making measles one of the most contagious diseases known. To prevent spread, at least 95% of the population must be vaccinated. “Measles is not a disease where we can rest,” Morin and Leguerrier told me. “We need to be constantly vigilant.”

The COVID-19 Aftershock

So why the lack of urgency to get vaccinated? It is hard not to point the finger at COVID-19, which Dr. Morin believes “accelerated a vaccine hesitancy trend that already existed.” Leguerrier describes this period as the “aftershock of the pandemic”: routine vaccinations fell behind, health systems were overwhelmed, and as countries emerged from isolation, many were left with immunity gaps. Quebec, for example, experienced a larger-than-usual whooping cough outbreak this past year because the expected cycle was disrupted.

The issue now, however, is not a matter of availability as much as access. Leguerrier and Morin stressed that effective vaccination systems are in place, but the measles outbreak shows that they are not reaching everyone. There are real gaps apparent in epidemiological data—specific communities across Canada where vaccination rates are lower—not because of who they are, but often because of deeply-rooted issues of trust, access, and belonging. “Those little holes we have in our vaccine coverage, to me, are a bit like holes in our social fabric,” Morin said.

Disease outbreaks have a way of exposing—sometimes brutally—people that society has left behind. This is why, according to Dr. Morin, public health must not only focus on keeping the population healthy, but on keeping the social fabric healthy too.

Measles Is the Warning Shot

This outbreak has made one thing abundantly clear: public health officials can no longer assume that people will show up for vaccines. Measles is getting attention because it’s so transmissible that even tiny drops in coverage trigger outbreaks, but declining vaccination rates threaten the return of other diseases, too. Although diphtheria, whooping cough, and even polio may feel distant, they are not gone. If enough people skip vaccines, they too will return.

So, where does that leave us? To regain measles elimination status, Canada must boost vaccination coverage. But in a climate of widespread disinformation and deepening vaccine hesitancy, this is no simple fix. When I asked Morin how we rebuild trust, she pointed to finding common ground: “No one wants children dying. Everyone wants safe communities, and we can build on that.” She hoped it would not take more children getting sick to motivate population-level change.

Leguerrier emphasized the importance of access: “Historically, when we offer the shot to people, it’s not usually refused. It’s just about getting it out to people.”

Public Health is a Group Project

Both experts had messages for McGill students and the wider community that I want to pass on—as a reporter, but also as a community member invested not only in my own health and my community.

Leguerrier said: “If you are vaccinated, don’t take it for granted that you’re protected. Check your booklet, and go get the vaccine. Check your children. Check your partner’s booklet. Make sure you’re all vaccinated. Every small action, such as getting vaccinated, counts for the community.”

Finally, to you, the reader, particularly if you are working in or studying health: re-establish dialogue. Connect with the community you are serving and bring the science with humility. As Morin put it, “We need to think about trust as an important determinant of health, and vaccination as one of the greatest challenges of the next century.”

Rebecca Winkelaar

is a fourth-year BSc Ecological Determinants of Health student at McGill University. Her research with Dr. Maheu-Giroux focuses on global patterns of HIV-related stigma through data analysis and visualization. She participated in the Global Health Scholars Program in 2025-2026 and currently serves as VP Advertising for the Canadian Association for Global Health at McGill. She is especially interested in bridging research and storytelling to make global health more accessible.