Short Term Experiences in Global Health (STEGHs): The mistakes we made, the lessons we learned and how we are moving forward

By Zoe Atsaidis and Lily Yang with the CCGHR Executive Team (Claire Norman, Sonya Madan, Alice Nam, Sara Marier, Aidan Cruickshank)

In January of 2020, we decided to cease operations of the McGill Chapter of an organization that sent students on Short Term Experiences in Global Health (STEGHs). After much reflection and discussion on the ethical considerations we came to realize how STEGHs without revision propagate the inequities in global health. Additionally, we have realized that it is crucial to document our mistakes in order to discourage future students and practitioners from doing the same, and also to highlight the existing colonial structures that perpetuate global inequity at various levels. Our effort as students is to make institutional change towards being more conscious and accountable in global health. As we highlight our missteps, process of realizations, corrective actions, we also welcome ideas and thoughts from the global health community on how we all can improve both as individuals and as institutions.

The history of global health is complex to say the least. It is crucial that we reflect on the history of global health when describing our current structures and practices. Global health is a field that is built on colonial roots with a history of exploiting vulnerable communities while perpetuating stereotypes of more affluent practitioners as saviors. Beginning as a practice whose purpose was to protect white European colonists from infectious diseases, the colonial roots of global health and sentiments of this origin still permeate the field today. Despite best intentions, people often unwittingly become involved with organizations that reinforce these colonial structures. In fact, at many institutions practices that mirror colonial scientific research are still valued and are regarded as high level qualifications to gain access to their programs.

Our Story

Our journey in global health began with our involvement as undergraduate students in an organization that coordinated short term mobile clinic trips abroad. These were 8-10 day trips to low-resource areas in South America where students worked with local doctors to provide medical care. As two students who were very interested in health equity and medicine, we thought this was a great opportunity to gain invaluable experience while also helping the global community. On these trips, we were primarily responsible for seeing patients, taking medical histories, taking vital signs, and giving prescriptions of vitamins or ibuprofen. Everything we did was supervised and verified by local doctors. Naively, our work seemed responsive to local community needs and didn’t seem to raise any ethical issues. In hindsight, our privileges, biases and Western gaze prevented us from recognizing many issues of concern.

For one, we were not trained in healthcare service provision, yet we were acting as healthcare practitioners. In Canada, our work would not be allowed without at least several months, if not years, of training. In contrast, for the short-term medical elective trip we only had a two-hour pre-departure training. In addition to this, there was no mandatory ethics or cultural competency training prior to these trips by the sending organization. Although most students attended these trips with the belief that they are providing a service, this lack of training leaves room for culturally insensitive behaviour, a lack of respect for the country, and a reinforcement of a “savior” mentality, among others. Finally, our trip placed minimal focus on the long-term well-being of the communities that we visited. Once communities finished their small bottle of free vitamins, their lives were likely not any better than before we arrived.

After our international trip, we both decided to join the McGill chapter of this organization’s executive team and eventually became the co-presidents for the 2019-2020 Academic Year. It was in this position of leadership that we began to understand the potential consequences of our actions and the responsibility we had to properly educate ourselves. In the Fall of 2019, we started to learn more about global health through our coursework and began to question the utility, ethics and the overall place of such trips in the global health landscape. Unsure of what to do, we contacted McGill Global Health Programs (GHP) and met with Dr. Charles Larson and Ms. Stephanie Laroche-Pierre. They addressed our ethical concerns and solidified our doubts regarding how these trips perpetuated systemic inequities. Gaining institutional support was a huge step in our efforts to reflect and take corrective action.

This meeting marked a turning point in our global health leadership, as we knew we had to make an important decision regarding our future with this organization. Ultimately, we knew the right thing to do was to cease our involvement and end further club activities in order to take a step in the direction and to stop perpetuating the colonial structures that contribute to inequity. Throughout this process we understood that we had to communicate our concerns and but also needed to remain cognizant of differing viewpoints, previous work, as well as those still choosing to be involved in the organization. Specifically, we sent out formal communications outlining our reasoning to all stakeholders (i.e. the parent organization, our executives, old leaders of the McGill chapter, general members) in a transparent but respectful manner. This was followed up with personal conversations with past and current executive members - all while actively communicating with and receiving guidance from McGill GHP.

Moving forward, learning from both our experiences and our course work, we wanted to contribute to global health in a more thoughtful, critically reflexive and equity-centered way. As a result, we established the first McGill chapter of the Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research (CCGHR)* with the guidance of GHP. Ultimately, our hopes with this organization are to create a community of learning for students and promote global health participation in an ethical, effective and equity-minded manner.

While STEGHs without proper ethical, cultural and sustainability safeguards are harmful, we do believe in recognizing the shortcomings of existing global health structures and refining them to create avenues to support communities in sustainable, ethical ways while respecting in-country regulations. We believe that the following considerations, while not providing solutions to all STEGH-related challenges, are crucial starting points to initiate steps to deter the blind continuation of inequitable practices.

Considerations for STEGHs

The following are some of the most important points we believe should be taken into consideration when creating or contemplating a STEGH. These experiences have particular ethical implications and challenges that apply to various stakeholder groups, including patients, host community collaborators, trainees, as well as the sending institutions.

Stakeholder Perspectives

Patient Perspectives

Firstly, it is important to consider the impact of these trips on the direct recipients of care. Studies reported that patients of several different short-term medical mission (STMM) clinics believe in their value for communities in which there are few healthcare resources available. This is particularly due to lower costs, access to medicines, availability of health care workers, and convenient locations. Patients reported high satisfaction with STMM and hoped to continue to see their services in the future.5 They also claimed that STMMs had a reputation for high quality of care.

However, published data examining perspectives of recipients of care and host communities is still very limited. Several pitfalls to these studies have been identified such as response bias (for example, participants may assume that survey administrators are part of the clinic staff, and therefore are prompted to give more positive evaluation), communication difficulties and potentially harmful deferral of treatment due to patients perceiving STMM clinics as superior to local services. Similarly, patients may feel inclined to give more positive evaluations due to inherent power dynamics between providers from high-income settings and recipients in low-income settings.

While much of the data collected from patients suggests STMM clinics excel at providing high quality care, areas of improvement to the operations of these services include wait times and approaches to communicating treatment plans. As the situation is complex and nuanced, further research, as well as the perspectives of other stakeholders, need to be considered when discussing STEGHs.

Host Collaborator Perspectives

The opinions of Low- and Middle-Income Country (LMIC) collaborators participating in STEGHs are often underrepresented in the global health literature. This prevents accurate evaluation of the impact and consequences of STEGHs in host communities. Despite studies reporting excellent patient satisfaction with STMMs, LMIC professionals working with sending organizations feel that there are limited benefits and significant drawbacks to these programs.

Moreover, interviews with host collaborators have demonstrated a perceived inequality between High Income Country (HIC) visitors and LMIC hosts. Notably, they discuss a lack of consideration for host contributions and culture as well as no increase in the quality of healthcare as a result of the STEGH. For example, Kung et al. reports that there appears to be differential treatment and provision of opportunities between North American administrators and LMIC collaborators. Additionally, host collaborators from this study state that their contributions to HIC trainee experiences were unappreciated as many trainees stopped contact and did not share results after being introduced to research projects by these LMIC professionals. This observation follows the unfortunate trend of “parachute research” in global health academia wherein researchers “[drop] into a country, [make] use of the local infrastructure, personnel, and patients, and then [go] home and [write] an academic paper for a prestigious journal”. Despite STEGHs providing some benefit to patients and LMIC collaborators, there is a harmful inequality between HIC and LMIC STEGH participants and an inconsideration for the work contributed by LMIC professionals who make these experiences possible.

Trainee Perspectives

While the impacts of STEGHs for trainees may seem purely positive, there are important considerations to be made. Firstly, students may lack experience and perform clinical tasks that are above their level of training. This may not only compromise patient safety but also result in stress and potential guilt for the trainee. Similarly, some students have reported a lack of training and mentorship prior to their STEGH. This was reflected in some of our own personal experiences with the trips, as many of us felt underprepared heading into our clinical duties. Finally, students looking for STEGHs have reported a lack of guidance in selecting an appropriate location for a global health placement.

Despite this, many students consider global health placements to be a positive experience. Such experiences have been described as an opportunity for cross-country comparisons, concrete skill learning, learning about how international health organizations function, and networking, among others.

In order to address these concerns and support the positive effects of these trips on students, program structure, guidance and mentorship should be considered as well as teaching the importance of reflective practice. Having students reflect critically during and after their experiences may improve learning and understanding of the larger ethical, moral and social issues surrounding their STEGH.

Legal Implications

In some STEGHs, participants may engage in activities that would be considered illegal under the laws of both the host country and their home country. These activities may include medical professionals practicing outside their scope, medical trainees participating in clinical activities without proper supervision, and volunteers being involved in patient care with little to no medical training. Trainees practicing medicine without an appropriate license is an offense in several countries, including many LMICs which require temporary licenses for visiting healthcare professionals. Despite this, some authors suggest that this frequently does not occur with STEGHs. Abiding by local laws is an important step to improving standards of care for patients.

Furthermore, there are legal concerns surrounding the free provision of pharmaceuticals. This practice is found in some STEGHs and has been discouraged by both the WHO and the FDA. Laws in both the home and host countries related to the distribution and prescription of pharmaceuticals can be evaded when being administered by a STEGH organization outside their country. Moreover, it is often unqualified students distributing the free medications which adds another layer of questionable legality to this already ethically dubious practice.

Looking for ethical and effective STEGHs

A fair amount of literature offers ethical guidelines for best practices in STEGHs to maximize benefits for host countries while also providing learning opportunities for students.

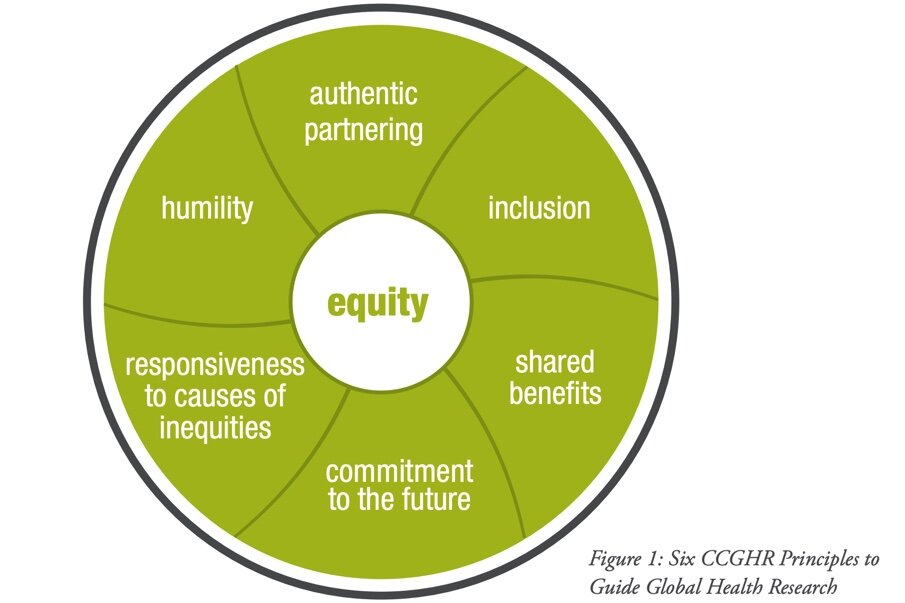

According to Melby et al., educational STEGHs should consider (1) skills building in cross-cultural effectiveness and cultural humility, (2) bidirectional participatory relationships, (3) local capacity building, and (4) long-term sustainability. Studies have emphasized the need for extensive pre-departure training including training in cross-cultural communication, as well as the sociopolitical climate. Other important principles include respect for local practitioners, respect for ethical and legal standards, programming defined by the host countries, and regular evaluation of the programs for impact.16 Finally, much of our knowledge is grounded in the CCGHR principles which serve as a framework towards identifying ethical and equitable opportunities (see Figure 1)

When considering a STEGH, students should look for organizations that embody these principles. Namely, they should consider those that offer extensive training on cross-cultural competencies, have long standing bidirectional partnerships with host communities, and ultimately are focused on sustainability and capacity building, so that local communities can continue to grow independently.

Our Recommendations:

Before participating in a STEGH, do your research. It can be really exciting when an opportunity to travel and experience medicine first-hand comes your way, but not all STEGHs are equal. Before committing to one, use all the resources available to make sure it achieves the intended objectives in the least harmful and most ethical way. Ask questions like: What is their mission? Will they offer extensive training? Is it clear that they are trying to uphold ethical standards and are focused on benefiting the local communities? This can be done by looking through their website, reaching out to professors or practitioners in the field, or perhaps talking to people who have been there before.

McGill offers longer term trips and courses that can teach you about global health while also having an impact. These courses and trips are often embedded in a long term project within the community that will continue to help even after you leave.

Understand your role on the trip. A STEGH can be great for encouraging young students to enter the medical field and pursue a career in global health, but remember that you will be there primarily to learn and observe. Often students believe that they will be making life-changing impacts on their trip, however the reality is these trips often benefit the students more than the host patients.

Students should also remember to demonstrate cultural competency on these trips, and be respectful of local practices and beliefs.

Reflection and humility Some STEGHs can be problematic as they may perpetuate a “savior” mentality, and a lot of students (us included) hold biases that they may not be aware of. Western values, attitudes, media and even our academic institutions often portray the Western world as being the pinnacle of health practices and everything else as lesser. Locals know the needs of their community best and they also know the best means of achieving that. When global health practitioners set up programs in other communities, it is less about helping them and more about providing them with resources that they may lack. Students attending these trips need to be aware of this and constantly reflect on their own biases. As mentioned previously, reflective practice is key to making the most of your STEGH.

A 2017 survey conducted by Cherniak et al., found that almost all local practitioners ranked trainees having cultural sensitivity, humility and teamwork skills as much more important than any technical skills.18 Before, during, and after your trip - humility and introspection are of the utmost importance.

Look into other ways of getting involved. STEGHs are not the only way to pursue opportunities in global health. Other ways include joining a research lab, participating in a club or starting your own initiative.

In addition, there are many local global health opportunities that you can get involved in. At its core, global health is about health equity, and regrettably health inequity exists in every community. You can get involved with local clinics, soup kitchens, advocacy groups and other initiatives (such as CCGHR) that aim to combat these inequities and injustices.

Concluding Note

We hope that this discussion of the missteps we made, corrective actions we took and actions we aim to take will serve as a resource to deter similar mistakes, especially by students but also by institutions. We understand that we have a huge task ahead of us in building equity in global health. Therefore, we welcome your ideas, agreements and disagreements on the subject. Global health practice and research is extremely valuable, and we hope that our reflection may inspire conscious and informed involvement.

*The CCGHR has recently been amalgamated with the Canadian Society for International Health to form the Canadian Association for Global Health.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr. Charles Larson and Emily Kocsis for their revisions, support and guidance.

About the Authors

Zoe is completing her MSc in Experimental Surgery and entering her first year of Medicine at McGill. She aspires to practice as a physician conducting global health research and is interested in infectious disease and endocrinology. Along with Lily, she co-founded the McGill branch of CCGHR and co-led the executive team.

Lily is a second year MSc student in Epidemiology at McGill and also completed a Bachelor of Science in Immunology at McGill. Her global health interests include infectious disease and access to care, and she is passionate about health equity. Along with Zoe, she co-founded the McGill branch of CCGHR and co-leads the executive team.