Hot Tips in the Cold: Lessons from Nunavik

By Léa Larochelle

My name is Léa, and I am a third-year medical student. Throughout my medical education, I have developed a strong interest in global health, driven by a desire to understand and address the social and health disparities faced by underserved populations. This interest prompted me to seek opportunities abroad, where I could gain firsthand experience and a deeper understanding of the challenges in healthcare delivery, particularly in remote and rural areas. My clinical rotation in Nunavik provided me with invaluable insights into the intersection of healthcare, culture, and geography, enhancing both my medical knowledge and my commitment to improving global health.

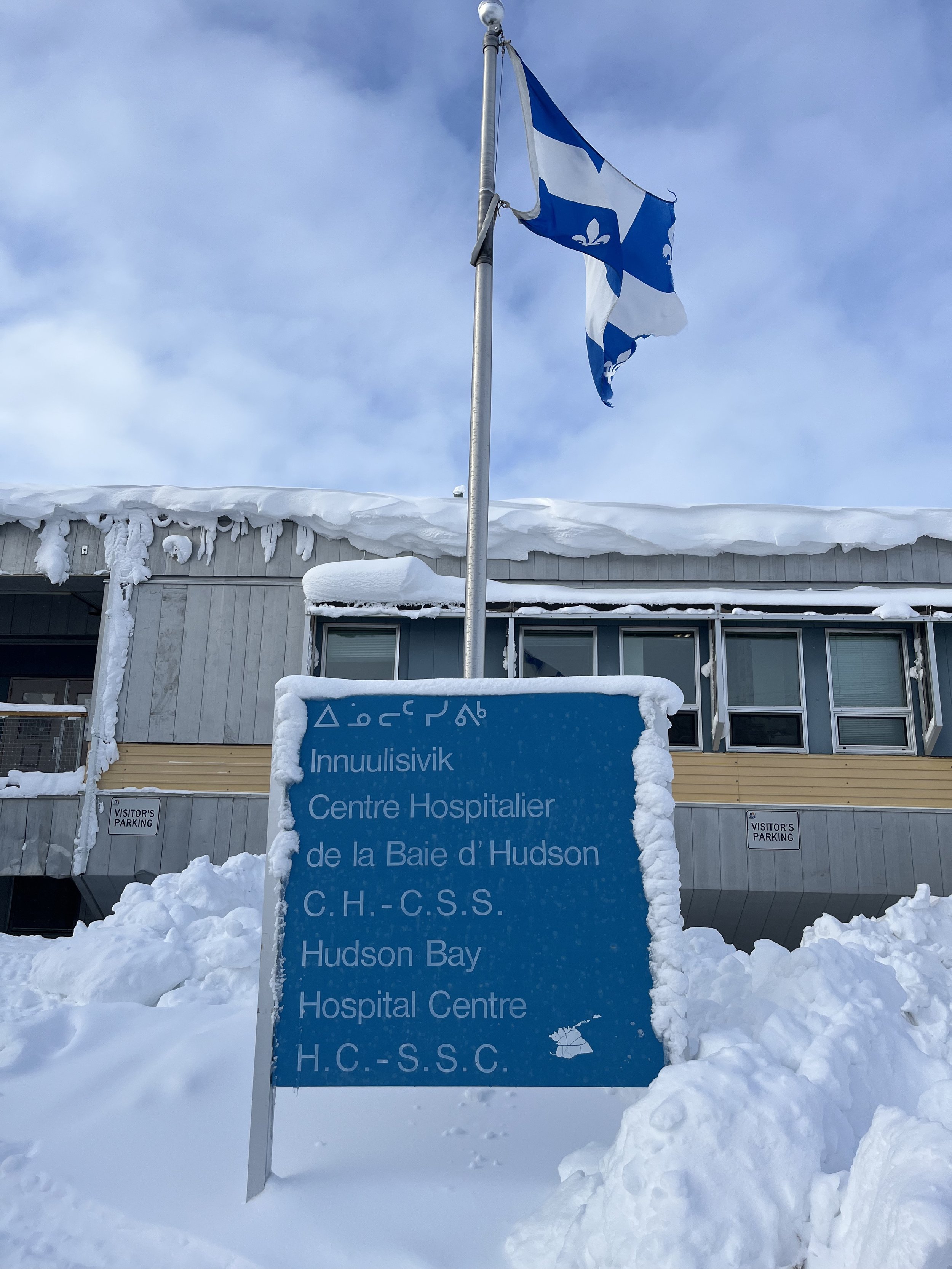

For my rural family medicine clinical rotation, I spent one month in Puvirnituq, a northern community in Quebec, working at the local hospital that serves villages along the west coast of Nunavik. During my rotation, I was involved in a range of activities, including providing care for hospitalized patients, assisting in emergency cases, and conducting routine appointments. Additionally, I had the opportunity to visit two other villages to assist in repatriating unstable patients for more specialized care.

Reflecting on this experience, there are several key lessons I wish I had known prior to my rotation. First, understanding the high prevalence of adoption within the Inuit community and the complexities of the foster care system would have better prepared me to navigate the social dynamics of the community. Second, gaining a more in-depth knowledge of the provincial and federal social, financial, and rehabilitation programs would have allowed me to provide more tailored, informed care to patients. Finally, having a greater awareness of the health risks associated with raw meat consumption, a staple of the Inuit diet, would have allowed me to provide more culturally sensitive guidance on food safety.

In addition to these lessons, several experiences during my rotation shaped my perspective on global health. One such moment occurred when a father brought in his three young daughters for a pediatric follow-up. Despite the language barriers and uncertainty about the reason for the visit, I saw an opportunity to teach the family about dental care. Through simple visuals and gestures, I demonstrated proper brushing techniques and explained the importance of regular dental care. At the end of the visit, I provided each child with a toothbrush, toothpaste, and educational materials. This experience reinforced for me that often, the most valuable care we can provide is not in the form of a prescription, but in offering essential health education that can have a long-lasting impact. Another significant experience occurred when I witnessed a patient experiencing preterm labour. Through telemedicine consultations, specialists in Montreal were able to provide real-time guidance to the on-site medical team, allowing them to administer life-saving care. This demonstrated the transformative potential of technology in healthcare, particularly in remote areas where access to specialists and resources is severely limited. It underscored the importance of innovation in bridging gaps in healthcare access and improving patient outcomes.

While my time in Nunavik was enriching, there were challenges that I had to overcome. One significant obstacle was navigating the delicate balance between providing medical education and avoiding the perception of criticism. Due to a history of mistrust toward non-Indigenous healthcare providers, my suggestions could easily be misinterpreted. Moreover, the community has limited access to education on topics like sexual health and preventive care, which made addressing such issues even more sensitive. To overcome this, I focused on building rapport by practising cultural humility, actively listening to patients, and delivering care in a way that was both respectful and responsive to their needs. Another challenge arose from the reliance on family members and close acquaintances as interpreters, which, while practical, sometimes introduced biases and affected the accuracy of translations. Additionally, the close-knit nature of the community made issues of consent and privacy more complex.

Reflecting on my experiences, I have identified five key takeaways that will shape my future approach to global health. First, it emphasized the importance of adapting medical practices to the unique cultural, dietary, and environmental conditions of the community. In Nunavik, I encountered health challenges specific to the region, such as a higher prevalence of alcohol-related health issues, domestic violence, and poor dental care. Understanding the context in which these challenges arose allowed me to provide more effective, culturally competent care. Second, the experience underscored the importance of flexibility in healthcare delivery. Unlike in southern Quebec, where protocols are often more standardized, healthcare in Nunavik required constant adaptability due to resource limitations and unpredictable weather conditions. Third, I learned the importance of respecting generational differences in healthcare discussions. Younger generations were often more open to conversations about mental health, substance use, and contraception, whereas older generations held more traditional views, which made these discussions more challenging. This highlighted the need to approach each patient individually, meeting them where they are in their understanding and providing education in a non-judgmental manner. Fourth, the role of midwives in the community was indispensable, particularly in childbirth, where traditional methods sometimes conflicted with Western medical practices. I learned that effective communication and respect for these traditions were essential to providing comprehensive care that patients felt comfortable with. Finally, I observed the challenges posed by the high turnover rate of healthcare professionals in remote regions. While short-term rotations bring valuable expertise, they can hinder the development of long-term relationships and continuity of care, which are crucial to fostering trust and improving health outcomes in the community.

This fieldwork experience has not only influenced the trajectory of my future career but has also reshaped my understanding of what it means to be a healthcare provider. It revealed the limitations of a one-size-fits-all approach to medicine and emphasized the importance of listening before leading. It has emphasized that effective healthcare extends beyond clinical expertise, requiring a deep understanding of the unique needs and values of each community. As I progress in my career, I am dedicated to pursuing a path that combines clinical practice with advocacy, focusing on sustainable healthcare solutions that empower underserved populations while respecting their cultural traditions and autonomy.